Editorial

Gian Luca Amadei

Pritzker prize-winning James Stirling was the architect behind Britain’s most famous post-war buildings. The most prestigious architecture prize in the country is named after him, yet his work continues to divide opinion. Ahead of a major exhibition at Tate Britain later this year, Anthony Vidler writes about the archive and legacy of an architect who remains Britian’s most important modern architect. Accompanying his essay, Blueprint asked eight leading international architects how encounters with Stirling’s buildings and the man himself have influenced them and their work. With contributions from Richard Meier, Odile Decq, Kengo Kuma, Peter Wilson, Antonino Cardillo, Kjetil Thorsen, Kersten Geers and Pier Paolo Taburelli, the responses reveal Stirling’s international reputation and an insight into how his work is interpreted outside the UK.

- Richard Meier

- Odile Decq

- Kengo Kuma

- Peter Wilson

- Antonino Cardillo

- Kjetil Thorsen

- Kersten Geers

- Pier Paolo Taburelli

Article

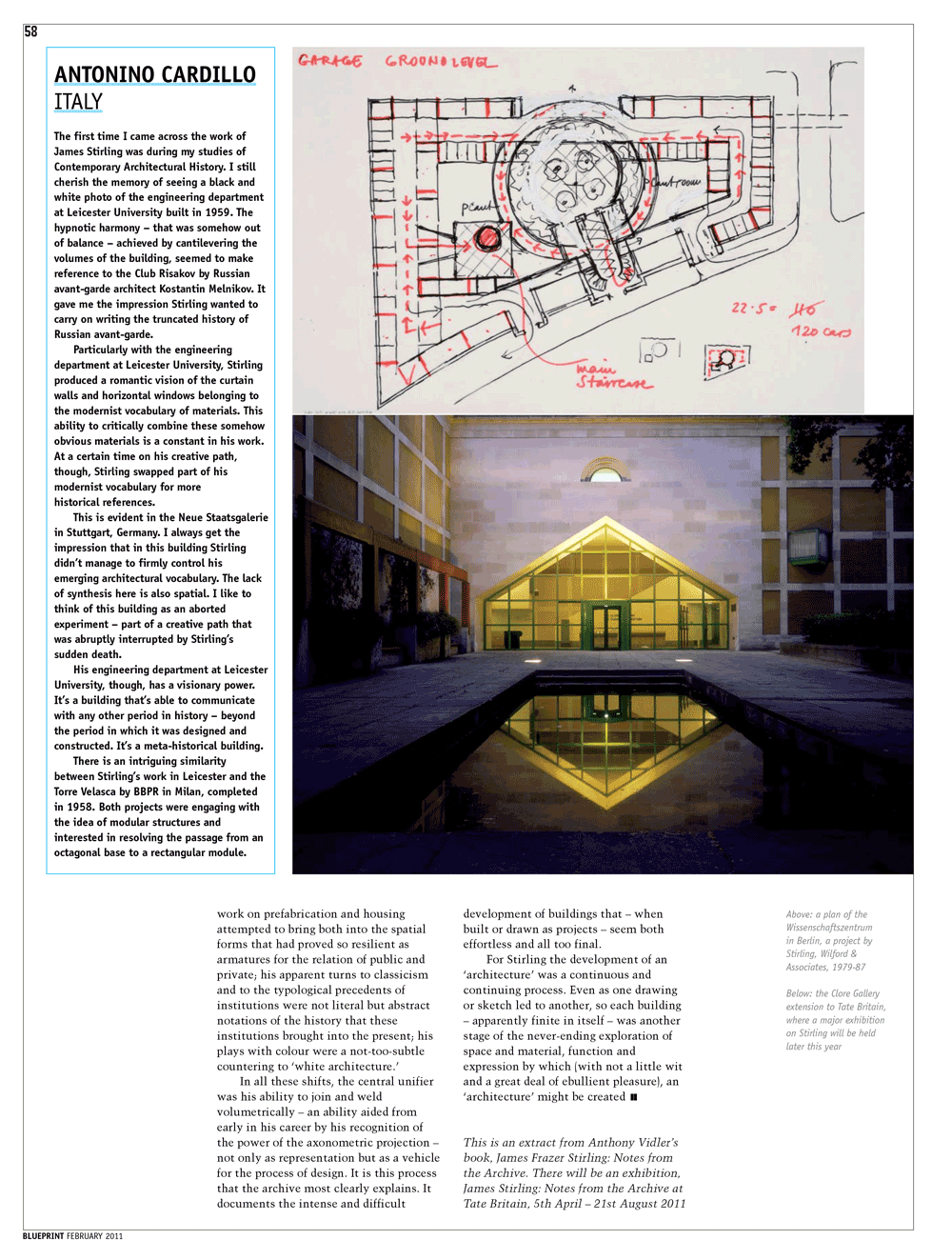

Antonino Cardillo

The first time I came across the work of James Stirling was during my studies of Contemporary Architectural History. I still cherish the memory of seeing a black and white photo of the engineering department at Leicester University built in 1959. The hypnotic harmony—that was somehow out of balance—achieved by cantilevering the volumes of the building, seemed to make reference to the Club Risakov by Russian avant-garde architect Kostantin Melnikov.

It gave me the impression Stirling wanted to carry on writing the truncated history of Russian avant-garde. Particularly with the engineering department at Leicester University, Stirling produced a romantic vision of the curtain walls and horizontal windows belonging to the modernist vocabulary of materials. This ability to critically combine these somehow obvious materials is a constant in his work. At a certain time on his creative path, though, Stirling swapped part of his modernist vocabulary for more historical references.

This is evident in the Neue Staatsgalerie in Stuttgart, Germany. I always get the impression that in this building Stirling didn’t manage to firmly control his emerging architectural vocabulary. The lack of synthesis here is also spatial. I like to think of this building as an aborted experiment—part of a creative path that was abruptly interrupted by Stirling’s sudden death.

His engineering department at Leicester University, though, has a visionary power. It’s a building that’s able to communicate with any other period in history—beyond the period in which it was designed and constructed. It’s a meta-historical building.

There is an intriguing similarity between Stirling’s work in Leicester and the Torre Velasca by BBPR in Milan, completed in 1958. Both projects were engaging with the idea of modular structures and interested in resolving the passage from an octagonal base to a rectangular module.

The page 58 of the 299 Blueprint issue.